When boats were made of paper

One of the joys of living near the Hudson River is seeing the rowing clubs plying their sleek craft across the water at dusk and dawn. The Hudson has long been a favorite of rowers, and for a few decades after the Civil War, it was home to a race-winning curiosity: the paper boat.

In the golden age of the inventor, restless creativity abounded. Elisha Waters had a cardboard box factory in northern Troy near the old State Dam. He was always on the lookout for new markets for his products, from match boxes to bra cups.

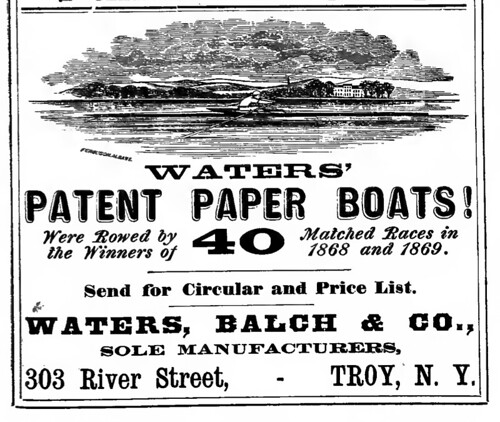

The story is told that his young son George needed a mask for a masquerade ball, but balked at paying high store prices. He borrowed a mask for a model from which he would mold his own mask, using paper pulp from his father’s box factory. How he made the leap from masks to boats is recorded in the style unique to the age: “‘Cannot,’ he queried, ‘a paper shell be made upon the wooden model of a boat? And will not a shell thus produced, after being treated to a coat of varnish, float as well, and be lighter than a wooden boat?'” Whether his flash of inspiration was actually so articulate, in 1867, George struck on the idea of preparing paper so it could be laid over molds and shaped into rowing shells. The Waterses formed a new company with respected Col. George T. Balch, late of the U.S. Ordnance Department, and set out to prove their paper boats had the fastest lines on the water.

According to an 1871 history of rowing, “The paper sheets are moulded over wooden forms, in a moist state, and when dried, are taken off in a single piece, without joint or seam on either outer or inner surface, and thus causing the least possible friction, for easy and rapid passage through the water . . . The paper skin is finished with hard varnishes, and presents a solid, horny and perfectly smooth surface to the action of the water, unbroken by joint, lap, or seam from stem to stern. This surface can be polished as smooth as a mirror, if desired; it cannot be cracked or split like wood . . . .”

Odd though it may sound, paper then was substantially different from paper today. Rather than being made primarily from wood fibers, paper in the 19th century was made primarily from linen or cotton fiber. Worn out clothes were given or sold to the local rag man, who would collect enough quality fiber to sell to the local paper mill. (Of local note, Kirk Douglas’s father was a rag man in the textile town of Amsterdam.) Long fibers made a strong sheet, and laid up, sealed with resin and varnished, and in that way preparing paper wasn’t so different from preparing fiberglass or other modern boat materials. But even so, convincing the public that paper would float must have been a challenge. The new Waters, Balch & Co. embarked on a very modern public relations campaign, getting their boats placed with some of the top crews of the day, winning races, and being sure the word got out. Robert Johnson’s “A History of Rowing in America” notes that Waters, Balch paper boats “were pulled by the winners of fourteen matched races, in 1868, twenty-six match races during the season of 1869, (their second year in use,) and fifty in 1870 . . . .” As early as 1871, the company was putting out a 400-page catalog, featuring not only its boats and their accomplishments, but articles on rowing, training, setting up a rowing club and even making a boathouse.

In 1878 well-known sportsman Nathaniel Bishop published “Voyage of the Paper Canoe,” his tale of rowing the Waters 14-foot creation “Maria Theresa” from Troy (having arrived there in a wooden canoe from Quebec) to the Gulf of Mexico, which further promoted the virtues of Waters’ lightweight, durable craft: “I embarked in my little fifty-eight pound craft from the landing of the paper-boat manufactory on the river Hudson, two miles above Troy. Mr. George A. Waters put his own canoe into the water, and proposed to escort me a few miles down the river. If I had any misgivings as to the stability of my paper canoe upon entering her for the first time, they were quickly dispelled as I passed the stately Club-house of the Laureates, which contained nearly forty shells, all of paper.”

This was all during a forgotten boom in rowing – according to the New York Times, from 1868 to the end of 1870, boat clubs in the U.S. and Britain increased from 56 to 247, part of one of our nation’s periodic physical fitness crazes. Professional racing teams abounded, and the sporting public took tremendous interest in the outcome of regattas. The Times, crediting Col. Balch with the writing of the catalog, said that he “deserves the thanks of every man in this country who really wishes to see moral and mental health and beauty combined with physical.”

While George focused on the boat business, Elisha continued to search for other uses for paper, including the first paper can for oil, and he hit on the idea of making observatory domes from paper, installing the company’s first one for the Williams Proudfit Astronomical Observatory at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1878. The 29-foot diameter dome was a success, except that a large telescope was never placed underneath it, and in 1900 the dome was replaced with a normal roof; the building was modified several times and razed in 1959. Paper domes were also built for West Point, Columbia University, and Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute.

Every boom turns to bust. The Waters boat factory had a good 30-year run, even as other makers entered the market and gambling scandals in the 1890s killed professional rowing and public interest in the sport. But while preparing a shell for the Syracuse University crew in 1901, George Waters caused a fire with a blowtorch that burned the entire factory. Claiming losses greater than their insurance would cover, the Waters company never rebuilt and George died the following year, followed by his father Elisha in 1904.

(A version of this article was also posted at All Over Albany)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=3c78aaa8-1b89-47f9-9512-d027457cb403)

hey man, nice blog…really like it and added to bookmarks. keep up with good work