14,244 Days

Thirtty-nine years ago today, I woke up hung over for the last time. It wasn’t the first time I was done with it – done with the horrible physical feeling, done with the regrets, done with the promises broken to myself and others – but it was the last time.

Everything in my genetics, ancestry and family primed me to be the perfect alcoholic – probably even the rebellious part of my teens where I thought I was above all that, that I would never give in to societal forces and compromise my thinking for a fleeting feeling. I know people who actually managed to do that, and they have my unending respect. But I didn’t – once the opportunity was there, I took it. I said fuck it all, and fuck it all hard.

Surely, it was gradual at first, and there were rules. Having lost friends to drunk drivers, I don’t believe I ever drove truly drunk, even by the more lax standards of the time. It was social, always with others. It wasn’t, in high school, what anyone would have considered out of the ordinary. (Was I massively, still dizzy drunk during a morning tour of the White House in my senior spring? I was. That wasn’t inappropriate, was it?)

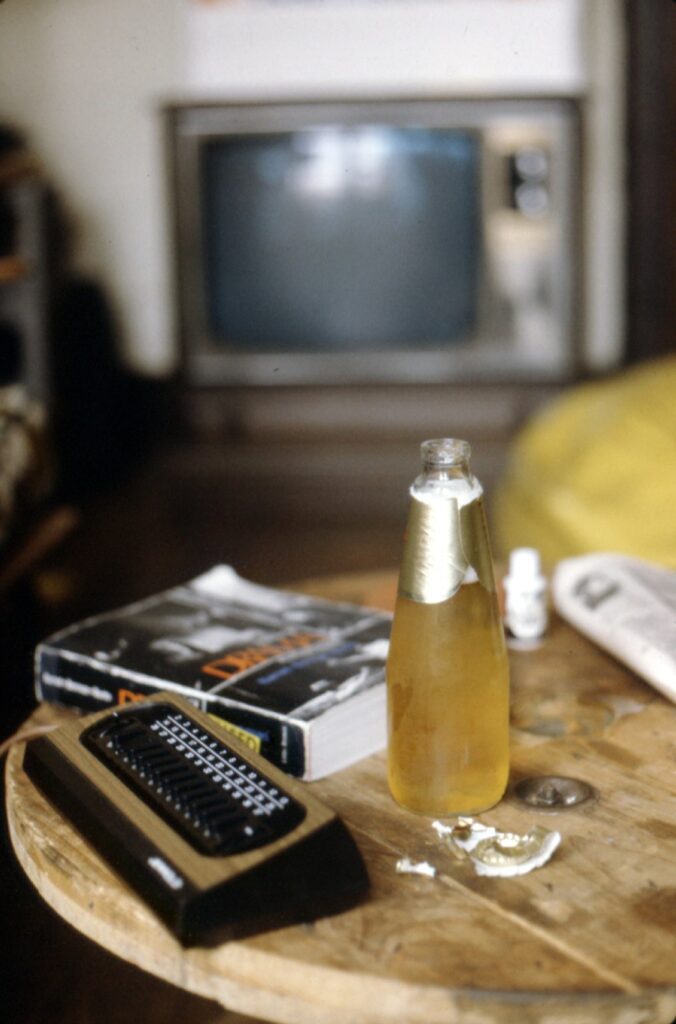

College, with its complete freedom and no need to hide anything, was different, and I lost control almost immediately, before my freshman year even started, really, with three weeks of unsupervised work-study experience that was binge-drinking with many older students by night, sorta working by day. Soon, drinking was married to ceremony – Annie Greensprings (or other horrible wine-adjacent beverage) nights on Tuesdays, rum and Coke night on Wednesdays (accompanied by long hours of Beatles records),and then whatever the weekend held. Friday happy hours at the incredible, iconic student nightclub on campus, Saturday nights chasing our favorite local bands, and of course college parties. The drinking was endless, my drinking particularly so.

There was other substance abuse (as it wasn’t called then), too – it was the ’70s, turning into the ’80s, after all – but that could come and go – it was the alcohol that was a constant. When drugs were among the things that helped ruin a relationship, I swore them off with ease, without regret, and I think never reneged on that promise. Why would I have to? I had booze.

I also had doubts, and disgust at myself. Reading some diaries from those days that are hard to read for a lot of reasons, I see how early I was aware that I was truly trying to drink myself to death. There were moments of lucidity, moments of clarity, even an entire semester of school where I behaved really well, some might say responsibly, for the most part. I recaptured my energy, my drive, my everything (except that relationship; that would come later), and my diary reveals that yes, I did know it was because my drinking was under control.

But that’s what it was: under control. And if something needs constant attention to be under control, it’s really not. And it wasn’t. My final year at college was a spectacular fail in so many ways, as I continued to spread myself so thin as to guarantee an inability to succeed at anything, except of course drinking, because I was a born master drinker.

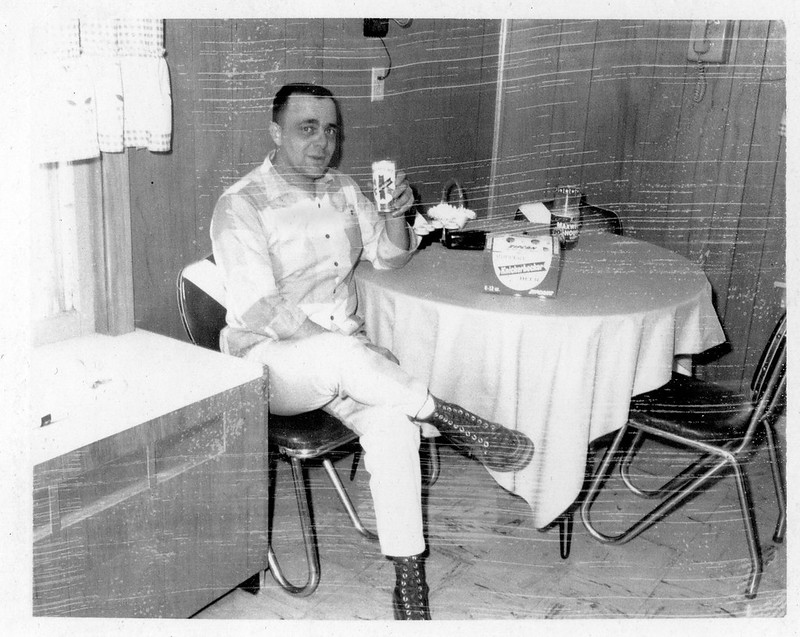

Again, genetically gifted in that direction. Everywhere I look in my family tree, wherever there is any information at all (and my family didn’t tell its stories, let alone give up its secrets), it’s a story of alcoholism. My father was at least a little drunk every single day of his life that I can remember. At some point when I was quite young he came home howlingly, embarrassingly drunk and proceeded to get sick, and my memory is of my mother (the only non-drinkers in my family were women, and not all of them) berating him for his condition until he was in tears. Whatever was exchanged between them, he never went that far again, but became very skilled at his dosages. After work he would, without fail, stop at at least one bar for at least one shot of whiskey and two to three to four beers before driving (yes, driving) the next few blocks home. I know, because I was often in those bars with him.

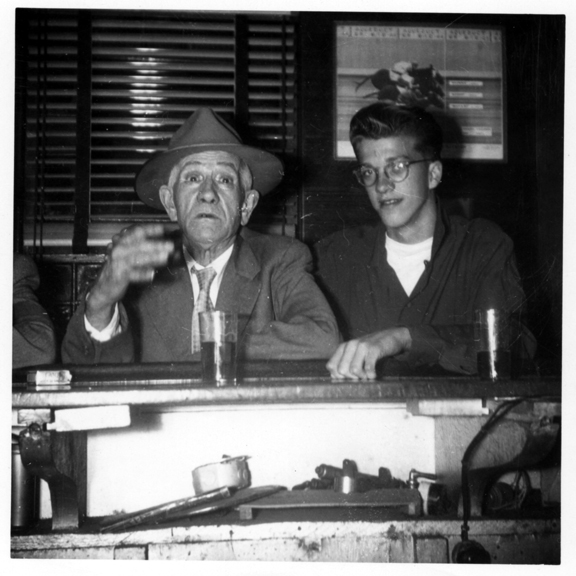

From the time I was 7 or 8, it was normal for me to accompany him on whatever errands he could think up that would also require that he stop by a bar before the errand was complete. I’d get a Shirley Temple at a table, that sweet liquory taste of grenadine, two or three quarters for the pinball or bowling machine, and maybe a Slim Jim for sustenance (never offer me jerky of any kind, thank you). Thus we’d blow away a Saturday or Sunday afternoon, before he would get in the car and drunk drive his elder child home. When I was older, I started doing odd jobs for one or two of the bars he frequented, and some of the other bar flies as well. It became a work environment for me. The hoppy scent of an ancient dirt-floored basement, saturated with decades of spilled beer, will never leave my nostrils.

His father? When my mother first met him, he had a black eye from being in a bar fight – when he was already nearly 70 years old. My mother’s father? Equally alcoholic (though another good maintainer), equally angry. My great great grandfather? A legendary drunk (and probably much worse – I suspect serious abuse) who would disappear on weeks-long benders across the countryside. Several of his sons? Also drunks. And those are just the ones I have living proof of – there’s plenty of other evidence, such as families that started out with founding stakes in colonial Connecticut and Long Island (not saying I’m proud of that) somehow ending up raking charcoal in the Adirondacks or with meager farm holdings in upstate New York.

So at least I came by my stupidity honestly, an ugly combination of nature and nurture. A whole lot of hurt, heartbreak and regret could have been avoided had I just never picked up the bottle, but that’s not what happened. A couple of years ago a friend in the alcohol counseling biz said that an inspirational speaker from a very, very famous family of alcoholics told her that, despite their family’s plight having been right up there for all to see, for decades, while some in the family took that as an object lesson, others were just moths to the flame. There’s no reasoning why. But I’ll say this: because my family was silent about it, about everything, and because society at that time barely discussed drugs or alcohol as a negative (unless they were drugs used by the “wrong kinds” of people, of course – our hypocrisy is always about race or trans control), I did not know that my family was riddled with this disease. Having grown up with it, I didn’t know my father wasn’t normal – if anything, I thought it was weird that other kids’ parents didn’t hang out in bars. That’s how immersion works, that’s how growing up works. You just think your own experience is the norm, and it takes a while to figure out that it isn’t. A long while, in my case. A real long while.

There were of course commitments to quit – sometimes when I’d gone over some self-set line, sometimes just out of recognition that this was no way to live. Sometimes I held out for a few days, never more than a week, and then resume with the thought that now I’d cut down, keep it in control, perhaps not drink every night. That’s pure folly, of course, and it never worked for long.

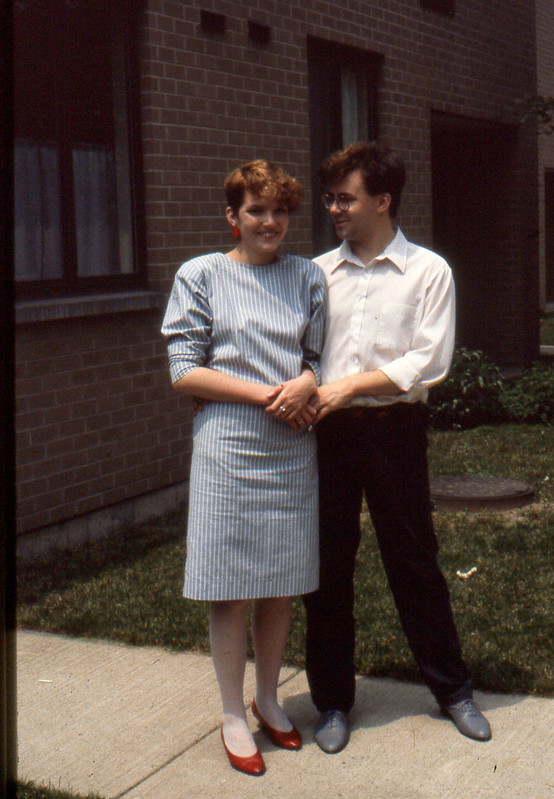

Then we were married, our college friends were drifting off into the world, and my drinking got even harder for a while. The amount of bottles we’d leave out on our stoop for the recycling pickup was truly embarrassing, and I knew it. I had a beautiful wife to share my life with, a challenging new job that I just loved and was thriving in, but every night I was getting absolutely hammered. I embarrassed myself at some gatherings with friends, completely out of control, and I had no real clue how to navigate the post-college world. It soon became clear to me that I wasn’t going to be able to drink my way through it. Even the novel I kept writing and re-writing in my belief that I would one day be a writer was about grief and booze and being old and alone, a fate I thought I was assigning to my father (and one that would have been true had he not taken such poor care of himself that he died at 48, an age I now see as impossibly young), but re-reading even some of those pages now it’s incredibly, painfully clear I was writing about myself. (It’s terrible writing, by the way. I have some stories from those days that I still think are pretty good, but that isn’t one of them.)

I tried to quit. I didn’t quit. I tried to quit. I didn’t quit.

I tried to figure out how to quit. This was before rehabs were everywhere, or anywhere – there was essentially one facility in our city, and it was for the hardcore cases. I did my research, figured out costs (no insurance), how long it would take, what it would mean. And while I did that, I tried to quit, and didn’t quit. I made a plan to ask my boss to front me the money for the program and let me pay it back through my paycheck (she absolutely would have, by the way, even though I’d only been with her a few months at that point). But I didn’t go to her, and I kept drinking.

Blackouts weren’t really my thing, they didn’t happen often – remember that I came from controlled alcoholics – but in the winter of 1984, I had two really embarrassing near-blackout experiences at gatherings hosted by friends, from which almost all that I could recall was a feeling of self-humiliation, that I had been just horrible to or near friends I cared about and respected. (That when I apologized years later, some of them didn’t even recall the incidents may say something about whether it was truly out of the ordinary, but it may also say something about their own states of mind at the time.)

And I don’t really recall the final trigger – some weekend drunkfest that left me filled with regret, shame, and anger that things weren’t different. And so I woke up and went to work on Monday morning, April 2, 1984, resolved that from there on out things would be different. If I didn’t make it on my own, I’d be going to rehab, but I was giving myself one truly last chance.

This is a long-held and hard-to-shake trauma response within me: just white-knuckle it. Don’t seek help, don’t tell anyone what I’m going through – just go through it. (I’m working on that, still, but I’m going to call that a combination of nature and – hmm, what’s the opposite of nurture? Oh, yeah: abuse. It’s the result of abuse.) I didn’t even tell my beloved wife anything in detail, and I regret that but that’s how it was, how it had to be for 23-year-old me to get through it.

The days were easy because I was working. The nights were filled with music and reading and some television, and the constant thought that if I could get to bedtime without drinking, that was all I needed to do. While I wasn’t in or interested in AA, I had read enough and was able to adapt some of the tenets that suited me, and one day at a time became one hour at a time or even five minutes at a time. When that nagging thought came into my brain that I should really take a drink, I knew that all I had to do was commit to not drinking for the next five minutes. I didn’t need to not drink forever, I told myself – I just needed to not drink now. I didn’t drink now for that entire work week, and when the weekend came, friends came over and hung out and we did things we usually did, but I didn’t drink. I think I just said I wasn’t going to drink that weekend, and that was it. Somehow I managed. Another week of work, and then the miracle of a second weekend without drinking. Once I had done that – gotten through two weekends – I knew I had won. And I had. I never drank again. Honestly, I’ve never even been tempted. In all the worst moments of my life since – and believe me, there have been some terrible moments – I’ve always had the thought that at least I’m sober.

I did get to tell my father that I had quit drinking, and harbored a fantasy that he’d see it could be done. I was living hours away at that point – once I left home for college, I never went back for long – and he was obviously happy that I’d gotten sober. In those days I still cared what he thought, which is now so bizarre to me that I can’t comprehend it, but at the time I still bought into society’s supremely damaging edict that you had to seek your parents’ respect and approval no matter what. You don’t – a parent can be bad. (And there can certainly be reasons for that – I often use the phrase “raised by wolves” to refer to my parents’ own upbringings, but that’s wildly inaccurate because wolves take care of their children – and either of them would have been safer with actual wolves.) In any event, he learned nothing, changed nothing, and died about a year and half after I got sober, thanks to years of abuse to his own body with alcohol, cigarettes and diesel smoke.

I’m mostly quiet about my sobriety. It’s useless to rail against this alcohol-fueled culture, and I’m tired of the part where I both have to explain that I don’t drink and then entertain questions about why. Reactions can range from genuine curiosity to people seeing my sobriety as some kind of threat to their own drinking (a super common response) – but I’m not here to shame anyone out of anything. Do what you do, don’t drive drunk, and I’m not going to care. But I’m also not going to be around it.

So now I’ve been sober for 14,244 days. 39 years. I’m proud that my children never saw me drink, that most of my friends today have never seen me drink. I’m glad that I do still have friends and acquaintances from the days when I was really just an awful person, that somehow they either didn’t see it or saw past it. I’m sure there are people from back then who saw me as I was and never wanted any more of me, and boy do I get that – I didn’t want any more of me, either.

I don’t follow the 12 steps but I do agree with some of them, including the part about making amends. I tried to do that to anyone I was still in touch with in the years when I first got sober – but if there’s anyone I missed, I am truly sorry.

I am living what is often a gloriously happy life, one where I have time and again been offered new experiences, new opportunities, new friendships. It has been and continues to be an incredible life. I had an experience just a few nights ago that opened my heart in ways I’m not ready to describe, that filled me with gratitude and appreciation for how good and beautiful people can be. And all of this is only because, starting on April 2, 1984, I didn’t take a drink.

Beautiful post. Many, MANY shared elements with my family and my own life and experiences, which I also do not often write about in public spaces. Painful stuff, hard to communicate. 39 years is amazing, truly. I have never been that successful or strong. A lifelong struggle, for sure, when nature and nurture are both in the opposing corner of the ring . . . . and you’re too busy punching yourself in the face instead of taking them on . . .

Much appreciated. One thing that’s tough about writing about it is that it necessarily implicates others, when the only behavior I’m really trying to judge or even present is my own. Struggle is okay, it’s giving up that’s a problem.