A Cabin in the Woods, and a Little Family History

(This also appears on my history website, Hoxsie.org.)

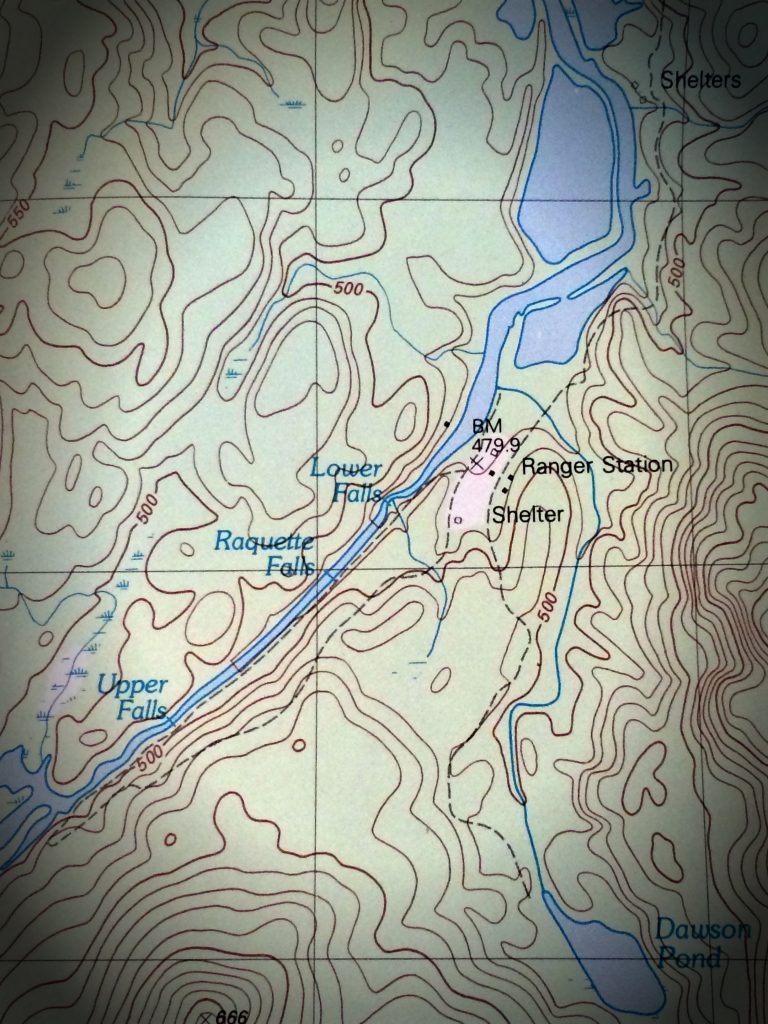

After years of good intentions but poor execution, of being somewhat nearby but never quite in the right area, I finally made it to the land of my ancestors last week. It’s a little tucked-away corner of the north central Adirondacks, far from any roads in the 1860s and not terribly close to any now. But at that time, the earliest tourists traveled by water routes from one end of the Adirondacks to the other, following routes set out by Seneca Ray Stoddard, Rev. Murray and other early advocates of wilderness adventure in upstate New York. (Remember that Verplanck Colvin wasn’t engaged to make a map of the region until 1872.) And as they paddled (or were paddled) down the Raquette River and came to the carries around the upper and lower Raquette Falls, their boats and gear were carried around the falls on an oxcart driven by my great great great grandfather, Philander Johnson, and they were fed pancakes and something that was acknowledged as trout when in season by my great great great grandmother, “Mother” Johnson.

It’s not entirely clear when they arrived there, though it’s likely it was any time between 1860 and 1865. It’s not entirely clear why they left Newcomb, where they had been tenant farming for a few years, and where their son William remained for a period of time. It’s not at all clear why they and the related families that they moved around with for a couple of decades didn’t move south even just a few dozen miles to a part of the world with shorter winters and soil that could grow something. Together, Johnsons, Pecks, Grahams and some others moved from northern Vermont to Crown Point, then into inland Essex County, making a stop in Newcomb before heading into deep wilderness to seek their fortune where there was none likely to be found.

I’m not quite sure when logging started in that particular neck of the woods, whether it had begun when they got there or whether they were entirely reliant on the little bit of tourism that was starting to build. It seems unlikely they could have made a go of it without a nearby lumber camp to serve, and it seems reasonable they may have gone there to feed the lumberjacks and found a profitable niche providing food and lodging to the big city swells.

Today, the closest paved road (well-packed dirt, anyway) is Coreys Road, which takes you to the head of the Raquette Falls trail (marked as the horse trail). It’s about 4.2 miles of pretty easy hiking (though with an amount of up and down) to reach the clearing where Mother Johnson’s stood. Today, there are two structures there – a nice modernish cabin built in 1975, occupied in the season by a ranger with the Department of Environmental Conservation, and an old, hand-hewn barn that could date back to Mother Johnson’s time. If not, at the very least it is known to have been there in 1890, so not long after.

We hiked in on a day with perfect overcast weather that later brightened up. When we got to the clearing, we met the ranger on the site, Gary Valentine, who has been there a dozen years and knew nearly as much about Mother Johnson as I did . . . which is really no surprise as none of this information has come down from family stories. It was only recently that I became certain that Mother (whose name was Lucy Kimball Johnson) was in fact William Johnson’s mother. Mr. Valentine gave us the grand tour of the new cabin on the site, and let us inspect the barn, marveling at the pinned construction with hand-hewn beams, speculating that it certainly could have been put up by Philander. In fact, he thought it likely, since the first thing new settlers had to build was a barn, not a house, as they would have to care for their livestock in order to survive. We can’t be certain, but it certainly makes sense.

We also talked about whether Mother Johnson was buried at Raquette Falls or somewhere else. The author Christine Jerome, in An Adirondack Passage, held that Mother Johnson had asked to be buried at Long Lake. That’s certainly possible, as it was the closest thing to a town nearby, but it’s also questionable as neither she nor any of the other Johnsons lived there. Her daughter Sylvia lived down the river at Hiawatha Lodge; son William had lived in Long Lake once, but had lived much longer at Coreys, and was by the time of her death likely near Westport, back east by Lake Champlain. There is a headstone at Long Lake that originally said “Old Mrs. Johnson,” then was turned upside down and re-inscribed “Mother Johnson.” But an article on her granddaughter Jennie Morehouse, in 1938, said that both Lucy and Philander were buried at the falls, as was Sylvia’s husband, Clark Farmer. In any event, there is no sign of any graves near the falls. There is a grave in the clearing where her lodge stood, but that is that of George Morgan, for whom a later Raquette Falls Lodge was built.

It was remarkable to sit beside the falls and think of how long people had been coming to that place in the midst of the wilderness, how the early Adirondack guides (including Lucy’s son William and then grandsons Charles and George) would have beached their boats above the upper falls and then hiked in to hail Philander with his ox cart, who would have carried the vessels around the falls while the “sports” enjoyed a meal and often slept over for the night. Likely those guides had to bring some of the supplies the Johnsons needed, such as milled flour, but it would appear that “Uncle” kept the guests in something like trout and “mountain lamb.” Even that early, there were hunting and fishing seasons to maintain the populations up. If, in fact, logging was already underway in that area, deer may have been hard to come by whether in season or not. Perhaps they had ice, but probably not. It was a hard, remote life.

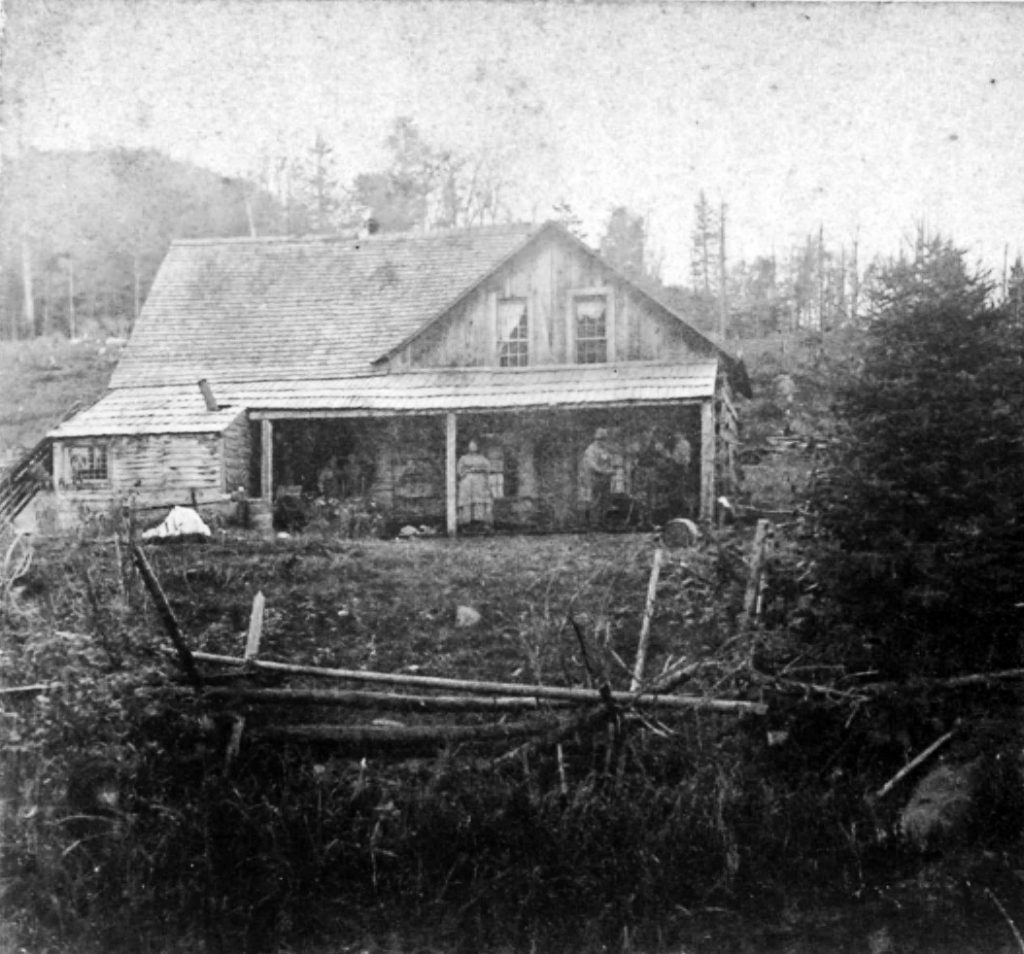

Think of what it took to even build a cabin in those woods. The land had to be cleared – at the time Seneca Ray Stoddard took the photo above, it looks like logging may have already occurred as the standing timber is intermittent. If the Johnsons arrived with the logging operations, then a logging crew may have made their lives much easier. If not, “Uncle” had a lot of work to do, along with whoever else from the families may have gone there with them. Once the timber was felled, it had to be shaped into beams using an adze – evidence of that handiwork remains in the old barn on the site.

This photograph of Mother Johnson’s, held by the New York Public Library, is undated. A guess of the 1870s can’t be too far wrong, as the house is complete and fairly spacious, with what appears to be a fairly lavish extension to the left of what was likely the original cabin on the right.

The construction itself tells a story of progress even in the woods. Besides the barn, which can’t be seen in this view, it seems likely that the first structure built would have been what is now the lower story of the cabin, on the right. It appears to be of squared log construction, and may originally have had a peaked roof but not one as high as the one in this picture. To the left is a little windowed structure with a stovepipe sticking out . . . this could have been a separate smokehouse (possibly a sugaring shack, but given the forest it seems less likely). That structure was sided with rough boards, meaning there was at least a planing mill somewhere near. By the time the spacious second story was added to the original cabin, better wood was available, as it is sided with dimensional boards and the windows are handsomely trimmed. It’s impossible to say whether the windows were assembled nearby from glass imported from elsewhere in the state, or if the sashes were brought in as finished pieces, but those are double-hung touches of civilization, in contrast with the multi-paned fixed window at the end of what we’ll call the smokehouse.

As business expanded, and more and more swells from the city needed a place to stay on their passage up the river, the Johnsons must have decided to simply add on to their cabin. When the upper story wasn’t enough, they must have added on that extension to the left, which likely had spacious common space down below and a bunkroom up above. Someone had the wherewithal to make some pretty nice-looking wooden shingles, and it appears that another stove was in use in that part of the house.

The stovepipe shows that at some point the oxen carried a stove in to the cabin . . . but from where? The first railroad into any part of the Adirondacks, built by Durant, only reached North Creek in 1871, a long, long way from Raquette Falls. The Fulton Chain railway, famous as one of the most popular routes, wasn’t completed until 1892. Saranac Lake, down the Raquette River to the north, was reached by the Delaware and Hudson in 1887, and the New York Central in 1892. So clearly, someone hauled that stove the hard way, a long way. The windows appear to be glass, which raises the question of where the glass came from, and whether the windows were crafted somewhere locally with glass from one of New York’s far-off cities, or if they were brought in as completed sashes. The logistics are daunting today, and seem impossible in the 1870s. But there they were.

Standing under the little shingled roof next to the center post is the ample frame of a woman who must be Mother Johnson. To the left, her right, are two men or boys in the shadows. They could be guides, they could be hired hands. Immediately next to Mother Johnson could be a dog. To the right, there are three men. Any of these could be Philander, or they could just be other Adirondack guides or the swells they catered to.

On the way out, we were treated to a ride down the river, an unexpected bonus that made me desperate to get back there with my own boats and paddle the beautiful, slow winding path of the Raquette below the falls. Our guide explained how it had been perfect for logging operations – in the early days, nearly all timber was moved by river, and some rivers were friendlier to it (and the loggers) than others. Today, it is a slow, lovely bit of water with sandy banks surrounded by grassy plains. There are several inviting campsites and lean-tos that are beckoning for a future visit.

May have attached comment- a request really – in the wrong place. Request is to reprint your work on Mother Johnson for the scrapbook of raq falls history that Gary Valentine started and we are still adding to. You are a far better writer than us. Also please visit again. Gary has turned over care of the place to my partner – kathryn Tyler.

P.s. i met Mary ( DeGarmo) Bryan there in late 60’s with my father- his mission was to ask her to turn it over to the State

Thanks! Yes, that’s the one I thought you were looking for. Sent you an email. And yes, I very much want to return, hopefully with one of my children.

And in case you didn’t get that email, yes, you have permission to reprint this. Thanks!