A father’s legacy

I don’t seem to be able to think of my father at the

I don’t seem to be able to think of my father at the

socially prescribed times, like his birthday or the anniversary of his death,

but Father’s Day is coming up and that has me thinking about my own legacy as a

father, and that makes me think of his as well. As the kids say, it’s

complicated.

He was a good man, and not a terribly good one. He was

generous to a fault, and wasted much of his life in bars. He knew how to build

things but lacked patience. He was inarticulate, uneducated, and embarrassed

about it, and he was massively proud that I turned out differently. He’s been

gone longer than I knew him, but even at the time he died I felt like I had an

incomplete picture of him, and not nearly enough memories.

What was expected of fathers started to change in the ’60s

and ’70s, when I was growing up, and so it’s fair to say that the transition

was confusing for many men. For a long time I just accepted that that was how

it was, and he definitely did come from a different time. He was one of ten

kids in a family where the father, 50 years old when my dad was born, was often

working in a distant city. There wasn’t a lot of father-son bonding. Or any, as

far as I know. So to my father, the amount of time we spent together probably

felt extravagant. But for the most part, it wasn’t time together; it was time

when he needed to go somewhere, and I’d come along. Mostly where he needed to

go was bars, the old dank neighborhood bars that barely exist anymore.

Sometimes there were other places: auto repair shops, the lumber yard, the

barber shop. We fished together a couple of times, and two or three times he drove

us on my scout troop’s annual trip to Lake Placid, but otherwise he wasn’t

there. It was up to someone else’s father to perfect my Frisbee throw or to

give me my first good fishing reel.

It seemed perfectly normal to me then, something any kid

might do, to accompany my father into bars and wait while he drank. These were

all places that knew him, where he knew everyone, and he was welcomed and

greeted. I learned later that a barfly’s welcome isn’t worth much: when he

died, people I thought were his friends couldn’t rouse themselves to come to

the funeral, but instead waved at the procession as we drove past the tavern.

But to him, these were his favorite places, and he probably felt sharing it

with me was a good thing. I’d get dimes or quarters to play the jukebox and the

bowling machine, I’d get the tiny glass of soda mixed with grenadine

embarrassingly and unfailingly called a Shirley Temple, and a bag of Wise potato

chips or Slim Jims. And then I’d just sit and wait and watch him leaning

against the bar, chatting with the other drunk men about nothing whatsoever.

And somehow I believed it was perfectly normal, despite the fact that I rarely,

if ever, saw another boy in those places.

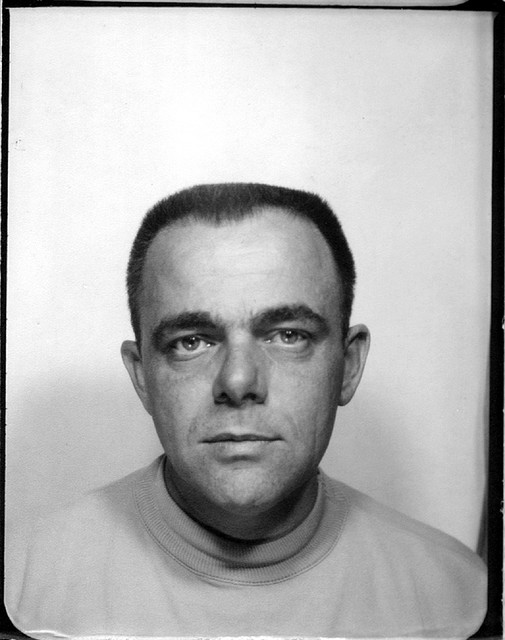

My strongest memories of him are the smells: the powerful

mix of diesel and cigarettes that clung to his work clothes, the whiskey and

beer on his breath at the end of absolutely every single day, the pungent cool

smell of stale beer soaked into the floorboards of ancient taverns. Images of

him are harder to find (and actual photographs, in a family that viewed film as

an exotic and unjustifiable expense, harder still), but to this day if I smell

rotting lettuce, which he often reeked of after a day of hauling produce for

Central Markets, I instantly think of my father.

He was sweet in many ways. He tried to be interested in the

things that interested me, and was always polite and kind to my friends. He

adored my wife and insisted she would have a wedding ring even though we were

too progressive to believe in such things. He was supremely willing to help

when help was needed.

He was stupidly young when he died, 48, and he died because

he drank and smoked, especially smoked, despite very bad asthma and a lot of

signs from his body that maybe it was time to straighten up. He didn’t. A few

years ago I found myself at his grave in rageful tears, so angry that he wasn’t

here to see his grand-daughters, and it was entirely his doing.

And so I think about the legacy, the memories my girls will

have of me. I lived nearly 18 years with my father, he died when I was almost

25, and as I said, even then my memories were scant. I have tried, not always

with success, to be present, to be there when I’m there, and not to be

distracted by the electronics and things that make it easy to divert our

attention. We have done a tremendous amount of things together, close to home,

around the state and even a bit beyond, and each one seems to elicit a very

specific memory for them, and I just hope those memories remain. I was blessed

with a period of time when I was home nearly every day, and we learned to cook

and bake together, to dance around the kitchen, and to just enjoy each other.

I’m touched beyond belief when my older daughter texts me with a question she

could easily have Googled, and when she thanks me for teaching her to solder

and how to wash dishes. I’m touched beyond belief when my younger daughter

squees with excitement that we’ll be returning to a campground we visited many

times when she was young and fell out of using, because I know her experience

of that place, and our being there together will always be with her.