All-nighters used to smell of hot wax and hypo

There’s stuff going on that has necessitated that, once again, I work the night shift. I’ll admit I had thought (hoped) that I was past the point in my life where I would watch the streetlights turning off as I left work . . . for the most part that seemed to be way in the past. It wasn’t. And while there have been various reasons for all-nighters through the years, including legislative all-nighters, this whole up-all-night thing started long ago with a technology that is long gone: offset print composition.

There’s stuff going on that has necessitated that, once again, I work the night shift. I’ll admit I had thought (hoped) that I was past the point in my life where I would watch the streetlights turning off as I left work . . . for the most part that seemed to be way in the past. It wasn’t. And while there have been various reasons for all-nighters through the years, including legislative all-nighters, this whole up-all-night thing started long ago with a technology that is long gone: offset print composition.

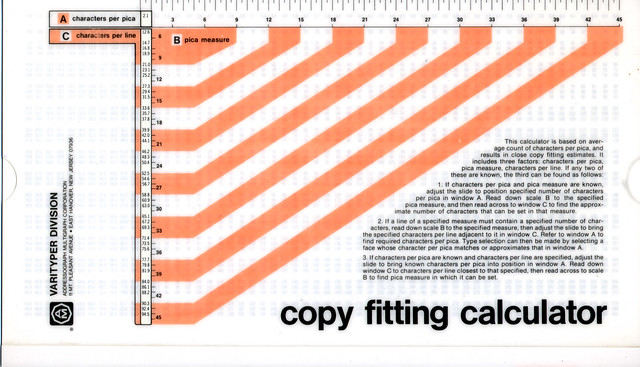

In the days before WYSIWYG computer-generated pre-press (do they even call it WYSIWYG anymore? Does that make any sense when it’s been a generation since there was any other way? Discuss), everything you saw printed on a page had to be created first on what was variously called a layout, composiition or paste-up. The type was all created on phototypesetters, which early on offered little or no editing capability. When doing the layout, which was the preliminary guide for how the publication should look, you basically had to guess at how much copy you would have. Sometimes that guess was good, sometimes it was bad. Sometimes it was incredibly bad. It was based on word counts from the typewritten manuscript, which were sketchy to begin with. You had to know your planned column width, then you used an average character-per-pica count from the font you were using, also pretty questionable, and tried to guess if the manuscript would be 13 inches or 30. It often ended badly, and in the newspaper business, the person responsible for getting the newspaper “to bed” would have to make decisions about what to cut. And those cuts were literal — there wasn’t time to reset the type. You just had to cut out the parts that weren’t going to fit, and if they weren’t at the end, it could make for some awkward-looking edits.

The type was on photographic paper. You’d have to trim the galleys (carefully), and then run them through a hot wax machine. Once the back of the type was waxed, you could put it down on the paste-up sheet, then line it up with a T-square to ensure it was straight. It wouldn’t stay straight for long, so you’d do that a lot. Line images would be created on Velox photo paper via photostat camera, and then pasted right in place. For the most part, halftones (anything with a gray scale) were handled separately, shot as negatives and inserted in the negative stage. Their place on the paste-up page was taken with a piece of red paper called a “window.”

Once the paste-up was done, it had to be shot as a negative, on film. The halftones were then stripped into the windows, essentially taped in place where the red paper had created a blank spot in the negative. Then you had to go over the negative with a fine brush and a clay-based paint, a process called “opaquing,” in order to get rid of imperfections that would print. Finally, the negative would be aligned on a piece of yellow paper called goldenrod, put into the position it would finally need to be on the press. Then the negative was exposed onto a light-sensitive emulsion on a metal plate, the plate was developed, and you had a plate that would be attached to the drum of the offset press.

In the newspaper world, this was an overnight process. It had a certain rhythm — waiting for the type, sorting out the layout sheets, pasting up what you could and waiting for the rest. Finding out that images weren’t the right size and having to re-shoot them (no clicking and dragging in those days). Finding out there was too much copy, or sometimes too little, and figuring out how to deal with it (and re-setting in another size was rarely an option, especially when it meant retyping the entire article and breaking style). There was the smell of the waxers, and the smell of the hypo that fixed the photo paper and stats. There was the loud vacuum noise from the photostat cameras, which used suction to hold the film on the platen. The low gear-turning motor sound from the developers, the quick high-speed whir of the waxers and the click of their switches. The satisfying snap of the T-square and the quick sound of the Olfa or X-acto slicing through the galleys.

This mode of composition lasted for a surprisingly short period of time. It was preceded by centuries of hot lead type composition that was done letter by letter, and a few brief decades of machines that could spill out lines of type at once (hence the Linotype), a massive technological improvement. Phototypesetting and that form of pasteup grew in the early 1960s. When I started paste-up in the mid-’70s, some work was still being done in lead because it was impractical to work it out in offset (such as numbering things like tickets, which relied on a clicking device that rolled over the numbers). In the few years that I worked in the field, we went from being unable to edit what we were typesetting, to being able to hold a buffer of two lines before committing it to type, to being able to store and edit entire jobs. We still couldn’t really see what we were doing in advance until about 1985, when the first machines offering some form of preview became common. They didn’t show you your type in its proper font, that wasn’t possible, but they were highly accurate otherwise. Then came the machines that started to let you do layout/pasteup in the machine. Then came Aldus Pagemaker, which meant that the whole thing could be done on a computer, and you could see what you were going to commit to print: WYSIWYG. In just a couple of years, pasteup was dead.

Even before that, I thought I was done with all-nighters. Apparently that wasn’t so.