Going Back, Part Five: The Embassy

I’ve been struggling for a while with how to tell the tale of my next residence in Syracuse, of my next year of school there.

Well, half-year. I’m struggling because it’s really the story of a highly self-directed, self-guided (which is to say, unguided), self-assured kid coming completely apart, without any real tools for understanding what was going on, or how to stop it. I’ve long thought of that year as the collision of alcoholism, drugs and the beginning of the Reagan era, combining into a giant “fuck this” attitude on my part. And it was all of that.

But what I’m just beginning to realize is that there was a driving force besides the addiction that I was not only unable to recognize, but that I was later fully convinced I had never suffered from, despite documentary evidence, in my own words, to the contrary. That driving force was depression.

For what happened in that year, alcoholism and my newfound willingness to top the booze off with drugs explains a lot. A lot. Economics will explain some of it, though the big crisis will come later. But there are things that even addiction doesn’t fully explain, like the nutritional abuse I inflicted on myself once we moved into a studio apartment without a proper kitchen, just an electric frying pan and a toaster oven – and while I was never a cook, I did understand nutrition, so I knew that a human being should not subsist on buttered rye toast, marshmallow fluff, and falafel mix. There was complete loss of interest in the very things that had been the center of my sense of self – writing and, to a lesser extent, photography. It all stopped. And now, I can see that depression had to have been the cause. But, this was 1980, and depression was something to hide and deny, and as a result wasn’t anything I would have been equipped to recognize in the form in which it hit me.

The apartment Danny and I moved into after Seneca was a not-terrible block of studio apartments in a newish (by comparison) frame building at the northeast corner of University and Harrison, which resembled nothing so much as a motel with an interior hallway. It was favored by foreign students, which is how we came to dub it “The Embassy.” It was owned by an architecture professor, so we figured we wouldn’t get too screwed on the deal (incorrect assumption). I almost broke the lease on day one when I got the keys and found our apartment unlivable, with shattered glass in the shower door and a number of other problems. Danny was already gone for the summer. The problems were fixed soon enough, but the omen wasn’t good. I might have taken the shattering as a sign.

Lee chose to live in the same building, which was convenient. She would have had a front row seat for my breakdown in any case. Our first summer there, 1980, was the Pig Book summer I wrote about last time, and most of my memories of that room in that summer involve the smell of SprayMount as I worked on pasting up the Pig Book and other publications at Danny’s big drawing table while listening to Phil Rizzuto getting progressively drunker during the course of Yankees radio broadcasts. I listened to a lot of Yankees that summer, as well as a lot of Syracuse Chiefs games, and we spent a lot of nights at the Chiefs stadium, MacArthur.

The school year came, Danny came back. I was doing my editorial page job at the Daily Orange with a new co-editor and friend and having a great time in that post. I suppose I was going to classes, though at this moment I’m not sure I could identify a single class I took that fall – an interesting hole in my memory.

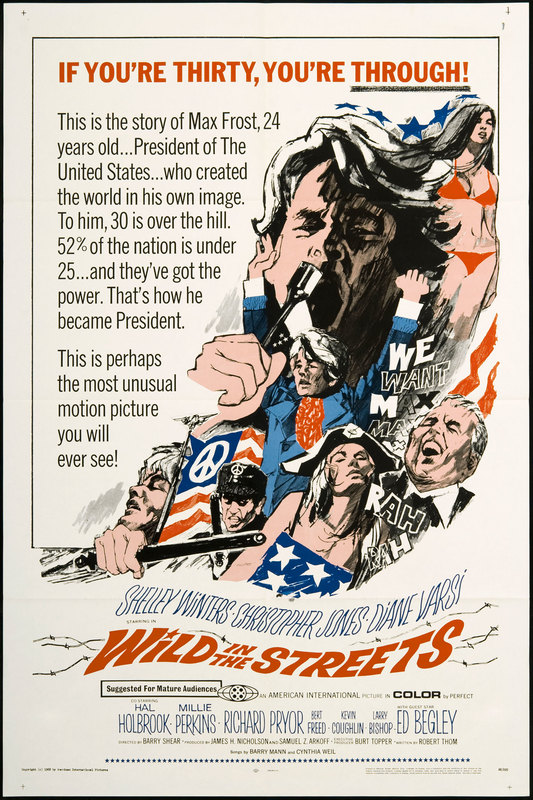

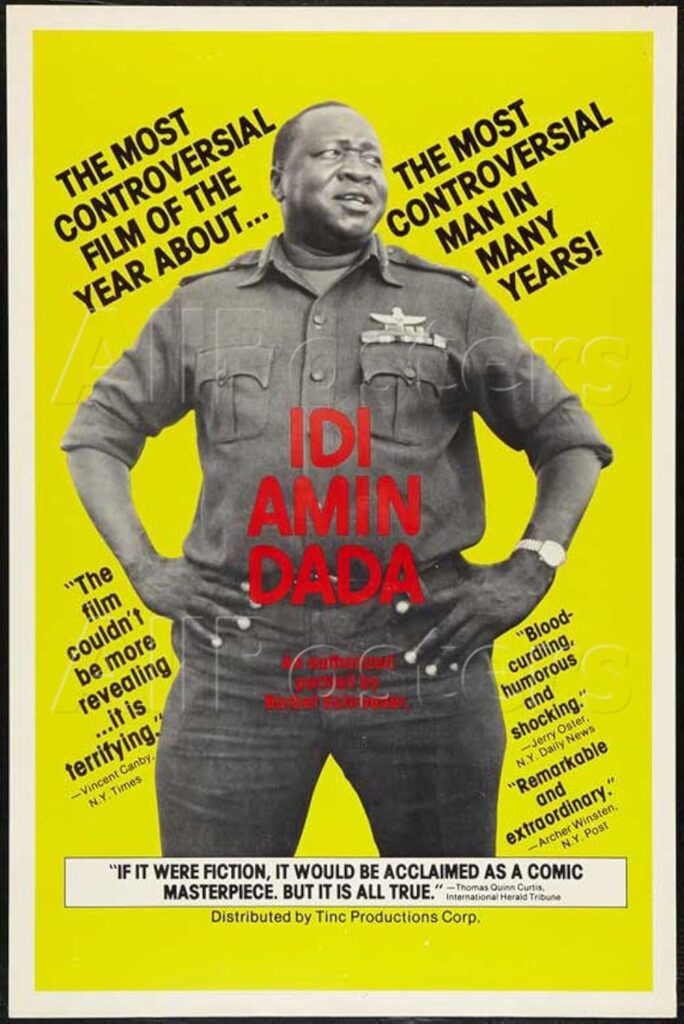

I was spending a lot of time getting high in my room, all by my lonesome, and listening intently to The Byrds, The Turtles, The Animals, and even some groups that weren’t named for fauna. One wall was adorned with a giant movie poster for “Wild In The Streets,” a 1968 American International flick I was moderately obsessed with despite having seen once (at a time when you couldn’t just watch something when you wanted to). It was mostly about the generation gap and lowering the voting age to 14, how groovy the youth movement was and how square the older generation was. The soundtrack was, and is, something else. I recommend it to no one, but it spoke to me at the time. In our bathroom hung a threatening poster of Ugandan dictator Idi Amin Dada – I’m sure I came by this one free at the DO, but why we wanted it hanging next to our toilet, I could not explain. It baffled all visitors – maybe that was the explanation.

That fall, I was already in a pre-crisis state regarding my future, as it was junior year and I was no longer sure I wanted to be a newspaper journalist. I also couldn’t really transfer out, as my scholarship, which paid nearly all my tuition, was specific to the newspaper program. Without that scholarship, there was no college for me, and not going to college had never been an option.

I was adrift, drunk, drugged and depressed. Yet, my memories of the time aren’t particularly dark. There was demonstrably life outside that little studio apartment – I had fun at my job at the DO, I remember there were great parties and life-giving shows at The Jab. But if I’m trying to picture that autumn, unlike other years and places we lived, I don’t picture Danny or Lee or any of our friends – all I see is me, sitting at my little desk, getting high and listening to “Mr. Spaceman.” I could not decide how to move forward. I could not decide to move forward.

Status: Full-Time Employee, Zero-Time Student

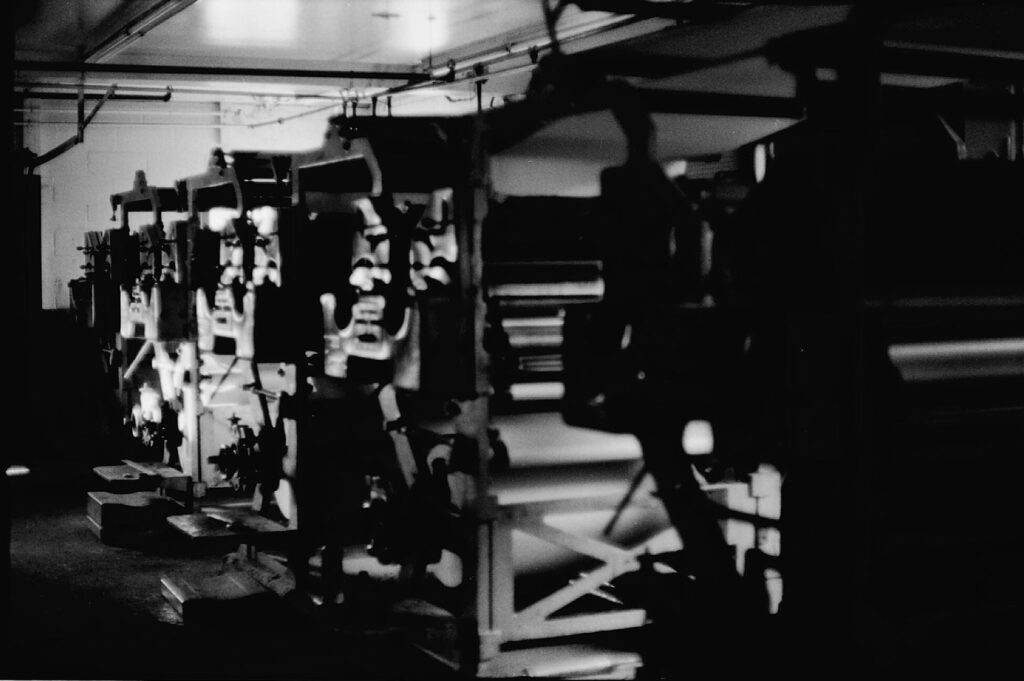

So I stopped. I took a break from school. When the fall semester ended, I went to work full-time for the printing plant where the DO was printed, eight miles away by Centro bus in Fayetteville. In terms of a break, of a sabbatical – well, the only thing I stopped doing that had led to me being so overwhelmed was school. I continued to work many hours, to drink and carouse and what have you. If anything, I now had more free time to fuck up my life and make bad decisions.

I started my newfound freedom, my life as nothing but a full-time employee, in the most depressing way I could imagine. Having just started, I had no choice but to work the day after Christmas. That meant a very brief visit home for our usual Christmas eve celebration, and then I would have to turn around and take the Greyhound back to Syracuse on Christmas night in order to be able to work on the 26th. I got back in very late on the coldest night of the year. I was just grateful the bus never broke down, but it was seriously cold out – minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit (-30 C). For one of the only times in my life, I was willing to pay for a taxi home – but as it was Christmas night and unimaginably cold, there was no such thing.

It was genuinely bone chilling. Mercifully, there was no wind. In fact, there wasn’t a sound. There wasn’t a car, a single sign of life as I made the 20 minute walk in the deadest silence and the bitterest cold I could remember experiencing. I was, I am sure, underdressed for it. By the time I got to our apartment, where I had not left the wall unit heater running while we were away, my teeth could not stop chattering. I got into bed fully clothed, took some ill-advised drinks from a bottle of some awful liquor that was lying around, and shivered myself to sleep. In a few hours, I woke up to a day no warmer than the night, shivered my way to the bus to work, and dutifully arrived at work to find almost nothing to do. If I’d been capable of crying then, I’d have certainly cried over the futility of it all, of the place I’d put myself in, of the pointlessness of this whole exercise. But I was a male brought up in the ’60s, so crying wasn’t acceptable. Inner rage was. It was encouraged, even.

It wasn’t a bright start.

What happened in the months after that, when I was out of school and working full time, is really a blur. When I visualize living in that apartment, I can’t separate when I was in school from when I was out – that all feels the same. No surprise, given how little I prioritized school at the time. My life outside the apartment was largely the same – nights at The Jab, sustenance from the Varsity in the form of pizza and sandwiches, horrible nickel beer and dollar pitcher nights at Hungry Charley’s. I gravitated toward spending a lot of my time with a friend who lived nearby, a photographer and artist and one of the funniest people I’d ever met, and it seems like cavorting around town with her and doing who knows what took up much of my time. Yes, there were also drugs involved – the Fay’s drugstore chain wasn’t the only one with the slogan “Not Your Average Drugstore.” That was how she answered her phone. But still and always for me, alcohol was first. I was paying terribly little attention to my romantic relationship, which suffered because I was both chronically wasted and never there, so that started to come apart too.

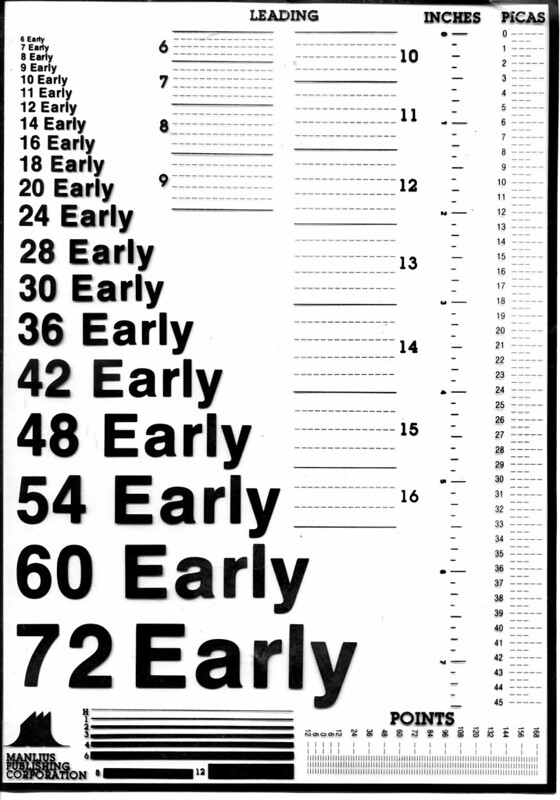

Working full-time in an antiquated, small-town web press facility, I was given a glimpse of another future I didn’t want. It didn’t quite oppress me then – the fear of being stuck there forever would come a couple of years later. I learned a huge amount about printing production (nearly every part of which has vanished from the earth now), and while I had gone into the job good at pasteup, already having done it since high school, I became an absolute marvel at it. It was beautiful, calming, satisfying, physical work, and never in my life have I been as good at anything as I was at pasteup. What I’d give to execute a perfect single-letter typo fix with an Olfa cutter and a drip of wax right now.

At the same time, I suddenly felt trapped in a world that was very old, very square. On my long weekends, I’d be out partying with young, fun people who seemed cool, interesting, full of life and ideas and futures, and then I’d take a slow Centro bus to Fayetteville and work in a depressing cinderblock dump somehow attached to a former house, and work putting together local newspapers from out of the 1950s among people I thought were waiting out their time to die. (Of course I’ve learned over time that people are not their jobs, that many people have fulfilling, interesting lives that aren’t necessarily apparent even to their co-workers. But as a 20-year-old fully indoctrinated in the absolute necessity of having an Important Career, what I saw in the lives of my co-workers was saddening, and represented absolutely nothing I wanted.)

Once I had left school, I couldn’t work at The Daily Orange anymore, but I was surprised when I was told that I wouldn’t even be allowed to write for it. I think I envisioned continuing to contribute humorous articles, which I had been running under a (literally) sophomoric pseudonym I’d used since high school so it wouldn’t appear I was just filling the editorial page with my own material, and so they wouldn’t undercut the “weight” of anything I was opining about on behalf of the paper. (I don’t know what to say about any of that thinking now, except that everything is so important when you’re young.) That meant that for the first time since high school, I didn’t have any kind of public outlet. I wasn’t writing, I wasn’t taking photographs. There’s not a single roll of film, not a single frame, from that year in the Embassy. Creatively, I was over.

So, I would work 40 plus hours in three and a half days, get a little drunk for the bus ride home every night (at the sad bar of a sad chain restaurant inside the entrance of Fayetteville Mall, where I waited for a 10:05 or 11:05 bus). Then I’d party throughout my extended weekend, get back on the bus, repeat. I didn’t make a new plan, didn’t figure out what I wanted to do with my life, didn’t figure out how to return to school, didn’t produce anything new – just worked and got fucked up. That I had given up everything that had defined me to myself just a few months earlier should have been a sign, or a billboard, or perhaps all of Times Square itself – huge flashing neon signs that something was seriously wrong. But I didn’t even see it. I wasn’t thinking of myself as addicted yet (as far as I can recall – but I’d even given up journaling as well, so there’s no evidence for this time period), and the idea of depression wasn’t even thinkable. Now, looking at that kid that I was, it’s almost all I can see.

Came late spring and it was time to decide how and where to live for the next year. Not only was The Embassy a depressing environment that only encouraged malnutrition, it ended up costing us way more than we’d been told to expect in utility bills. I couldn’t begin to say why Danny wanted to remain roommates –without my connections at the DO, the free Idi Amin poster supply had dried up – but he did, although he was going to be in Florence the next semester. And even though our relationship was sub-great at that point, Lee also wanted to share an apartment with us, and I had previously promised my co-editor, who had been in London and missed seeing my spring of debauchery, that she could move into any space we found for the next year. It’s amazing how things worked in those days – we had the conversation before she left in December, I would guess corresponded by postcard or air mail once or twice while she was away, and I was actually wondering if she would remember I had made the promise when we got the next apartment. But she did!

So it fell to Lee and me to find an apartment suited for four people (eventually), close to campus, where we could close out our college careers. As we did that, I still didn’t know whether mine was already closed. I didn’t know what to do. I was fucked up and exhausted and it wasn’t getting better. But at least it wasn’t in The Embassy.

I said I’d been struggling to tell the story of The Embassy, and how I felt to see that ratty apartment building still standing when so many of the places that were so much more significant to me have vanished without a trace. As I stood there in front of it recently, I really didn’t feel anything – of course, no fondness, but no particular vituperation either. It was just: there.

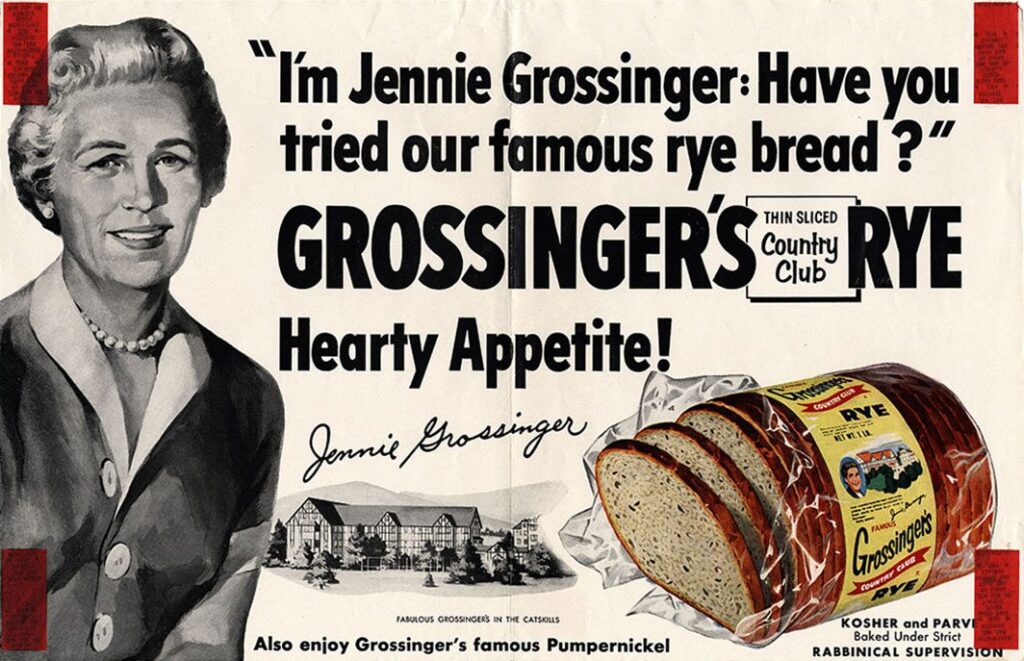

There’s where those things happened. That’s where I played “Mr. Spaceman” on an endless loop. That’s where I lived on Grossinger’s rye bread (which has never been equaled, it must be said). There’s the window I stared out of while pasting up publications, listening to Scooter get sloshed while I got sloshed. Up the hill and a couple of blocks over, there’s where my friend’s ramshackle apartment building stood (oddly replaced in the ’80s by a newer building bearing the same name, Toad Hall). These are the streets I ambled down at all hours of the night in some level of incapacitation or another, at some level of self-destruction or another. There’s the bus stop in the super-sketchy neighborhood where I would hop off the bus at 10:40 or 11:40 at night, and confidently but quickly make my way up empty streets to safer ground.

There’s where I came apart.

Well, not quite. But soon I would.