How Menands got its name

(A version of this was previously published at All Over Albany.)

So, what is a Menand?

Well, the question really is, who was Menand?

For the answer, you’d have to look back to the late 1800s, when

everyone from well-to-do collectors of exotic flora, to prosperous

homeowners with gardens, to cemetery visitors who wanted to pay tribute

to a loved one — would go to Menand’s.

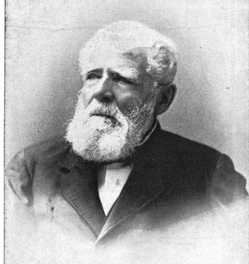

Louis Menand was

Louis Menand was

the son of a gardener in Chalons, Burgundy, France. As early as he could

remember, he was fascinated by horticulture. “I was eight or nine years

old,” he later wrote, “when I began to try to grow plants from

cuttings. I have always been fond of cutting, properly or figuratively

speaking, except cutting my fingers.”

Eventually Louis became an estate gardener in Paris and later in the

Champagne region. In 1837 he came to New York and went to work at

nurseries in Halett’s Cove, which would later become Astoria. There he

met a young piano teacher from Albany named Adelaide Jackson. They

fell in love and were married in her family home on Park Place in

Albany, and soon took up residence in what they called “the haunted

house” on the Albany-Troy Road (Broadway). Louis began selling

plants. After a rough first year (“more than modest, that is to say

meagre, I might say miserable!!”), things began to pick up.

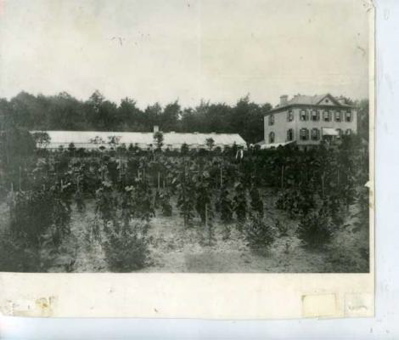

Menand had a fair collection of “hardy perennial plants,” which had

become pretty popular in the Albany/Troy area. Later he sold Norway

spruces, balsam firs and other popular trees and shrubs. In 1847 he

was able to buy several acres of land on what is now Menand Road, where

Ganser-Smith Park is now located, for his greenhouses and nursery.

He cultivated plants that, no doubt, had never before been seen in

this old Dutch town — camellias, palm ferns,

cacti, and orchids, among others. Forty years later, an article in The

Gardeners’ Monthly and Horticulturist would proclaim:

“It is Mr. Menand’s aim to exhibit at least one specimen of

every known variety ; and whenever a new one is produced in any quarter

of the world, it will not be long before it may be found at Menand’s.

Thus it often happens that persons who search in vain for rare specimens

in New York and elsewhere, are generally directed to ‘a crazy Frenchman

at Albany,’ where they are sure to find what they want and carry it

away, provided their purse is long enough. In fact, it is Mr. Menand’s

aim to furnish anything from a strawberry to a tree.”

He was noted for importing exotic plants from Europe, and commanded

an impressive price for his best camellias: “a little plant four inches

high would sell for $25.”

Menand won significant awards for his plants through the years, and

continued to grow. He bought 31 acres near the entrance to Albany Rural

Cemetery, where he set up his son with a half dozen hot houses devoted

to growing cut flowers, roses, carnations, pansies, geraniums and “an

almost endless variety of other species suitable for cemetery

decoration.” These included all manner of shrubs, which no doubt still

influence the scenery in the cemetery.

His greenhouses were so popular that the Albany and Northern Railroad

added a stop there in 1856, named “Menand’s Crossing,” which the

succeeding Delaware and Hudson Railroad renamed “Menand’s Station.”

Louis set about telling the story of his life in an autobiography,

with the snappy title, Autobiography

and Recollections of Incidents Connected With Horticultural Affairs,

Etc., From 1807 up to this day 1898 With Portrait and Allegorical

Figures. ‘By an ever practical wisdom seeker,’ L. Menand. With an

appendix of retrospective incidents omitted or forgotten.

The title is about as direct as the rest of the book, originally

published in 1892 and then updated in 1898. The ramblings of this

“crazy Frenchman at Albany” shed very little light on the actual events

of his life but give an incredible sense of the energetic character of

Louis Menand. There are exuberant paeans to his wife Adelaide (whom he

calls “Phanerogyne,” meaning “remarkable woman,” who died in 1890.

There are rambling thoughts on the various revolutions and republics in

France, a scathing appraisal of his arrival in a free land “where

slavery was flourishing as carnations,” and tales of intrigues at flower

exhibitions, all told in the least linear style imaginable. (The

version available here on Google Books includes several handwritten

notes by Louis.)

Louis Menand died in 1900 at the age of 94. It wasn’t until 1924 that

the apostrophe-free name of Menands became official, when the village

was incorporated.